|

| Alfred A. Knopf |

His interview was enlightening as it showed his process for fabricating stories, revealing his best tips and tricks for keeping up one's momentum, uncovering where he gets his ideas and why. I found it fascinating to see how he worked, to find out why he did what he did and why he created what he created - and it was nice to get a glimpse into his creative capacity.

So how does Roald Dahl create such interesting characters as Veruca Salt and Grandpa Joe? Well, for one, he refuses to write ordinary characters:

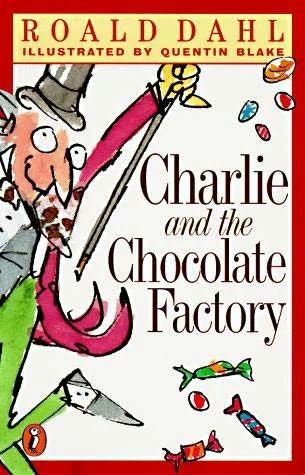

"When you're writing a book, with people in it as opposed to animals, it is no good having people who are ordinary, because they are not going to interest your readers at all. Every writer in the world has to use the characters that have something interesting about them, and this is even more true in children's books. I find that the only way to make my characters really interesting to children is to exaggerate all their good or bad qualities, and so if a person is nasty or bad or cruel, you make them very nasty, very bad, very cruel. If they are ugly, you make them extremely ugly. That, I think, is fun and makes an impact."Exaggeration certainly does make an impact in reading Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. It makes characters much more memorable. Furthermore, it sets distinct lines between "good" and "bad" - that is, it emphasizes the good qualities of characters (like Charlie, and Grandpa Joe) and the bad qualities of characters (read: Veruca Salt, Mike Teavee, etc.) and makes them more likable or despicable. It makes them unique and, like Dahl points out, makes it fun.

Moreover, I would think that the reader finds it easier to bear when bad characters meet an equally bad ending. When horrible characters meet a horrible end, it isn't always a tragic event. However, Dahl takes the added step of making horrific events less - well, horrific:

"You never describe any horrors happening, you just say that they do happen. Children who got crunched up in Willy Wonka's chocolate machine were carried away and that was the end of it. When the parents screamed, "Where has he gone?" and Wonka said "Well, he's gone to be made into fudge," that's where you laugh, because you don't see it happening, you don't hear the child screaming or anything like that ever, ever, ever."His argument makes sense. When left up to the imagination, it's hard to envision that Augustus Gloop would ever be made into fudge - it's impossible, right? - and it's even harder to imagine Violet Beauregard turning into a blueberry and being juiced. These events are never described in detail: you will find no gore, you will find no real violence; rather, you will see the effects much later - you know, after you realize his characters are indeed still alive.

And, I suppose, that makes terrible things - Augustus Gloop being made into fudge, Violet Beauregard turning into a blueberry, Veruca Salt falling down a garbage chute to the incinerator, Mike Teavee getting shrunk to the size of a person's thumb - easier to stomach.