- Read a nonfiction book about science.

- Read a book originally published in the decade you were born.

- Read a book with a main character that has a mental illness.

|

| Pegasus Books |

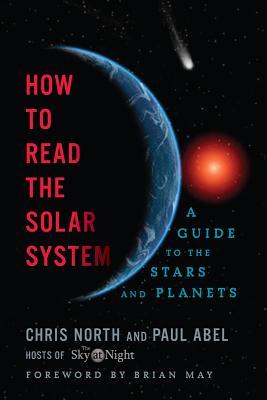

I'm not saying it wasn't a good book. I learned something interesting about each of the planets and the different heavenly bodies that inhabit space, which was an important aspect of reading this book. For instance, I learned that Io, one of Jupiter's dozens of moons, has tectonic activity (specifically cryovolcanic activity, since it's an icy wasteland); sound waves travel faster through plasma, which gives scientists the opportunity to measure the internal activity of the sun (since it's made up of plasma); and meteor showers are essentially the debris left behind by comets, like a dust storm that the Earth passes through during its orbit.

I enjoyed actually learning something new, even if it's not quite as useful as one might hope. Like I said, it's not a bad book. Just a little dry and dense and, dare I say it, pedantic. It's not something I would read twice, but it's a vast well of information that's sure to hold appeal for readers who greatly enjoy science, astronomy, technology, and even mathematics. It's definitely worth checking out, especially if you're curious about the solar system and the explorations humankind has made. More importantly, it gets a point in my book for having an index, so I was able to easily look up the most intriguing bits of information.

Next, I looked at The Professor and the Madman by Simon Winchester, which was more in line with my purview. Titled The Surgeon of Crowthorne when it was originally published in Britain, Winchester's book underwent a slight change when it migrated over to the United States, becoming The Professor and the Madman--which was accompanied by the glorious subtitle, A Tale of Murder, Insanity, and the Making of the Oxford English Dictionary. I mean, how could I not be the tiniest bit enticed?

|

| HarperPerenial |

As crazy as it might seem, it's all very true.

Like Erik Larson--who has written Devil in the White City, Dead Wake, and Thunderstuck--Winchester has a narrative quality to his work that makes it appealing without compromising the facts. Winchester pulls from a variety of resources, including medical documents from Broadmoor (an infamous mental institution for the criminally insane in Crowthorne), correspondence between Professor Murray and Dr. Minor and other important individuals, as well as historical texts. He uses information to benefit the story, supplying an electrifying narrative and, simultaneously, feeding his readers the true and unaltered facts. It's all very, very good.

As for my final book, I read The Lives They Left Behind: Suitcases from a State Hospital Attic by Darby Penney and Peter Stastny. Although I suspect this final category--which recommends reading a book with a main character who has a mental illness--is referring to a fictional novel rather than a nonfiction narrative, I decided to run with the ambiguous wording and read something not about one character with mental illness, but ten.

The Lives They Left Behind explores the lives of Willard State Hospital patients who were admitted to the hospital during the late 19th and 20th centuries. Penney and Stastny provides an in-depth look at some of the permanent residents at Willard, as well as offers a glimpse at the big picture of mental/psychiatric care during its formative years. The book also provides photographs and illustrations that further illuminate the care patients received, and what sort of trials they went through with (or, in some cases, without) mental illness.

|

| Bellevue Literary Press |

Altogether, I found it to be a fascinating book. It's an examination of psychiatric care that provides statistics, which can prove a bit dull, but it also connects on an emotional level and delivers nuggets of truth that are sometimes like a punch in the gut. It's a tough read sometimes. For instance, I had a hard time reading about the electroshock therapy that often caused patients to have convulsions, or the medications that were prescribed that often did more harm that good--or, worse, how some patients were treated even if they didn't suffer from a psychiatric disease.

Patients, like Ethel Smalls or Margaret Dunleavy, were most likely suffering from other conditions rather than mental disorder. Ethel Smalls likely suffered from PTSD after losing her children and being on the opposite end of her husband's temper, enduring years of abuse that left her in a fragile state. Likewise, Margaret Dunleavy was hospitalized after an uncharacteristic outburst due to a personal tragedy and chronic pain. Neither woman displayed the usual characteristics of mental disorder, rather they were hospitalized because they were inconvenient. It's a heartbreaking fact behind the stories of many patients.

No comments:

Post a Comment